Credit Suisse: What’s going on in the market?

On March 13, U.S. President Joe Biden reassured the depositors and employees of two large banks, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank, that their deposits were safe and that wages would be paid. More generally, President Biden reassured investors that the U.S. banking system was solid and the government was taking action to secure deposits.

The Biden administration had to work around the clock over the weekend before Monday March 13 to avoid a domino effect arising from the collapse of SVB. In particular, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp (FDIC) took over and replaced SVB’s management team while stepping in to shore up liquidity for its deposits.

Why SVB failed

The Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was founded in 1983 in Silicon Valley, in California’s Bay Area, and catered primarily to tech companies. SVB benefited from the rapid growth of the tech sector to the point that SVB became the 16th largest commercial bank in the U.S.

In the post-2008 era, with the Federal Reserve keeping interest rates low to stimulate the economy, SVB filled its coffers with pricey U.S. Treasury Bonds.

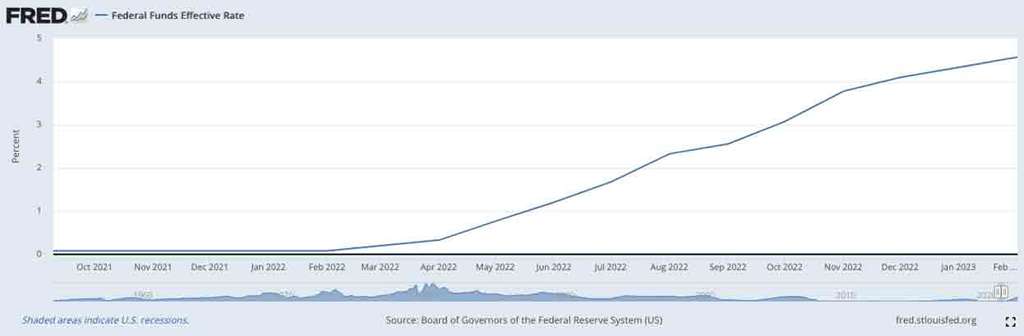

This year, the Fed gradually raised interest rates to fight inflation. The Federal funds’ effective rate (i.e., the overnight rate) increased from 0.08% in February 2022 up to 4.57% by February 2023. This caused a substantial drop in the value of Treasury Bonds, which meant that SVB was now sitting on a smaller asset buffer.

Yet, on the client side, rising interest rates increased the cost of money. SVB clients withdrew more from their deposits to honor their commitments and at the same time faced a harder time to raise venture capital, according to CNN.

This translated into fewer assets to back those deposits while liquidity was dwindling as clients withdrew their money. The impossibility of repaying the deposits triggered a run on the bank and its precipitous fall.

What does this imply?

The Biden administration had to intervene to avoid the domino effect. A bank that fails means deposits cannot be repaid (at least not immediately). This means businesses are unable to pay other businesses, which thus means other assets are lost and other banks are put at risk. The government’s quick intervention and the liquidity injection prevented more dominos from falling. However, President Biden was clear: direct investors are not to be protected. Investors took a risk: the risk pays off if that risk does not materialize, but pays nothing if it does. This is capitalism, President Biden was telling markets.

All eyes now on Credit Suisse

Investors then went around looking for who else was weak on the market, noted Ms. Smialek, a New York Times reporter with an eye on the Fed, in an interview, and they quickly spotted Credit Suisse.

Credit Suisse had been struggling to stay afloat for quite a while now. The institution faced several scandals, including a conviction on counts of money laundering by several former employees. The bank was also found to have “material weakness” by its auditor (PwC) especially in its investment banking division. According to Bloomberg, in 2022 many clients disserted the bank, especially in the growing Asian market, which had been a profit driver for several years.

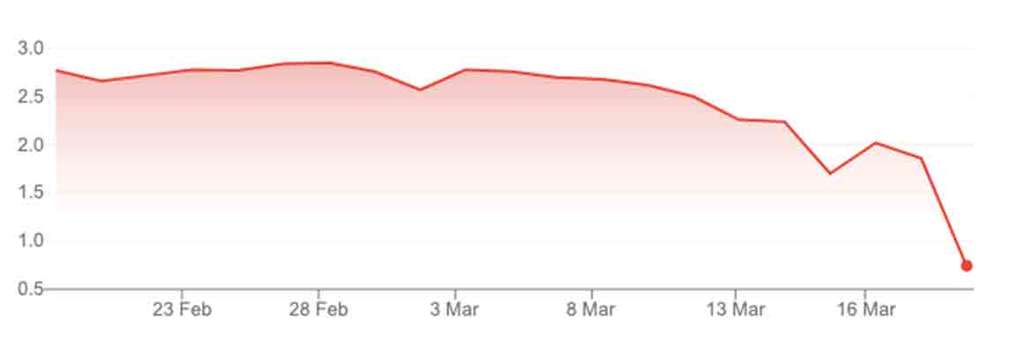

Credit Suisse’s largest shareholder, Saudi National Bank, was asked to inject liquidity into the struggling Swiss bank. It promptly declined, sending the bank’s share price tumbling. Where it traded at CHF 7.64 in September 2022, its shares were worth CHF 0.74 CHF as of March 20, 2023, i.e., a staggering 84% drop in market cap.

UBS will absorb Credit Suisse with the assistance of the SNB, which extended a line of credit to smooth the acquisition procedure. The SNB will back up the operation, ensuring a liquidity support of up to 100 billion Swiss francs.

This move should enable the market to breathe a sigh of relief and dispel the specter of another 2008 financial crisis. The fall of Credit Suisse, a bank of systemic importance to the Swiss economy, could have sparked a financial crisis on par with the demise of Lehman Brothers. It is thus no surprise that regulators around the world have welcomed the SNB’s swift move.

The implications

Although it is too early to judge the full impact of this deal; we can, however, state the following:

- Credit Suisse is a TBTF bank, the second largest Swiss bank and employs 50,000 workers around the globe and 17,000 in Switzerland. UBS’s acquisition comes with the aim of shrinking Credit Suisse’s core business (investment banking), or in the words of UBS Chairman Colm Kelleher: “(…) UBS intends to downsize Credit Suisse’s investment banking business and align it with our conservative risk culture”.

- UBS will be able to reinforce its position in investment banking. The takeover will allow UBS to target the Asian and American market while becoming “the world’s leading wealth manager with $5 trillion of invested assets”, according to CNN.

A word of caution

The collapse of Credit Suisse occurred because the alarm bells failed to ring properly. There is the feeling that FINMA’s detection of the problem was too little too late. Also, the fact that it is ultimately the SNB that is left to deal with the dirty laundry when the horse has already bolted, raises the question of the role of the Swiss watchdog and its firepower in preventing similar situations.

This is more alarming if we consider that the bank acquiring Credit Suisse is a bank that was bailed out by the taxpayers and the SNB just a few years ago following the 2008 financial crisis in similar circumstances. Adding pressure is the fact that the merger of two of the largest Swiss banks will now create one gargantuan bank, and if red flags fail to signal problems again, the room for maneuver will be very tight indeed.

EHL Hospitality Business School

Communications Department

+41 21 785 1354

EHL