Restoring Meritocracy in Hospitality The Case for a Talent Engine

Executive Summary

America's most important engine of human meritocracy is facing its biggest challenge ever. A generation of talent is leaving the hotel industry as brands are betting on franchising, delegating human capital management to hundreds of third-party managers who lack an employer brand. Reorganization, incremental improvements, and digitalization of the workplace are necessary but insufficient to fill 3 million annual openings. Radical innovation, supported by innovative technologies, is required to bring the hotel industry's human capital back to equilibrium. It starts with reimagining the role of HR from administrator to the creator of employee-first platforms such as talent marketplaces that advance meritocracy and accelerate diversity. CEOs and Boards of Directors can usher in the new paradigm with deal-making focused on establishing talent exchanges within the hospitality industry and like-minded organizations in adjacent service industries.

Hotel Industry as an Engine of Meritocracy and Growth

Few industries have a track record of generating economic impact and providing upwards mobility as hospitality. Overall, immigrants own 29 percent of all restaurants and hotels, more than twice the 14-percent rate for all businesses, according to U.S. census data. Consider the success of people of South Asian origin in the U.S. hotel industry. A majority of these owners are Gujarati, hailing from India, Pakistan, Uganda and elsewhere. It started in 1942 when a man named Kanjibhai Manchhu Desai left Gujarat, India in search of new opportunities. He was joined by two Gujarati farmworkers, and they took over a 32-room hotel in Sacramento, California, after the property’s Japanese-American owner was forced to report to a World War II internment camp. It was far from an overnight success and white competitors, especially in the rural south, put not-very-subtle “American-Owned” signs outside many of their hotels. They gradually expanded by acquiring more properties across states, focusing on the economy segment. By the 1980s, the second-generation kids of these immigrants started expanding the frontiers of their parent’s businesses. By 2007, they owned over 21,000 of the 52000 hotels in the U.S., or 42% of the market. Furthermore, they have expanded their management companies and launched real estate funds and publicly traded investments in full-service hotel segments in the U.S. in Canada led by Hersha Hospitality Management, Noble Investment Group, Vista Hospitality, and others. There were two key factors in their success: flexible “handshake loans” between members of the tribe to acquire hotels and a reliance on family as a key source of labor. Once a family purchased a motel, they would live there, and the family members would do all the tasks needed to run it, from cleaning rooms to checking in guests. There are many other examples of how the hospitality industry has created economic opportunity and upwards mobility. Refugees from Vietnam and Cambodia first arrived in Orange County by way of Camp Pendleton in 1975. Among them, there was a man named Ted Ngoy who would later be known as the "Donut King." This niche business created an economic pipeline for newly arrived refugees from Cambodia. By the 1990s, there were approximately 1,500 Cambodian-owned doughnut shops in California alone.

Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to replicate the success of these immigrants today, even on a regional scale. This is not because informal sources of capital have dried up, and not due to difficulties with the supply chain or more regulations. It’s because costs are prohibitive. Today, most hotel and restaurant chains have divested real estate and are imposing brand standards resulting in higher capital costs and higher fees. Anti-immigration sentiments are adding to a severe labor shortage, unionization is spreading across the service sector and most chains have walked away from their role in developing talent and acting as the lead human capital manager for their respective industries. Consequently, profit margins are being squeezed, capital costs are higher and labor is more expensive and scarce.

Brutal Facts of the Hospitality Labor Markets in 2023

As we enter 2023, hotel operators are on a losing streak in the talent markets. The same industry that has made significant progress over the past decade capturing the customer with direct bookings has lost 20% of labor market share to other industries. Ironically, these very savvy investors and operators have inadvertently made things worse for themselves by treating HR tech as an afterthought. Most operators continue to invest in advertising and social media on "big tech" 3rd party job sites and ATS platforms that use their funds to grow their own databases and perpetuate control of the talent markets. The good news is that much of this is within the industry’s power to change. The first step is to collect facts, analyze the problem's root causes, and quantify the gap between current strategies and the desired outcome. Consider these five brutal facts regarding the labor crisis confronting hospitality operators in the U.S. as we enter 2023:

Fact One: There are currently 1.6 million job openings in U.S. hotels and Quit rates are 2x the national average.

Fact Two: U.S. hospitality must hire 2.9 million people a year to reach equilibrium, including 1.3 million replacement hires.

Fact Three: Even in an optimistic labor market recovery with aggressive recruiting and labor efficiencies, the gap is still 2.4 million.

How can the industry retain and attract sufficient talents to close this shortfall? Consider an optimistic perspective where college graduates with fewer employment prospects join hotels in larger numbers (organic growth), the industry successfully adjusts its labor model to become more flexible, pay more competitive wages and eliminate some positions through efficiencies and service reductions. Let’s do the math and see where that takes us.

- “Bottoms up” Organic growth: Hiring new associate and bachelor’s degree college graduates, including hospitality schools. Challenge: even if hotels capture an additional 10% of the entire market of 2 million annual new hires, their turnover is 50%. Number: 100,000 gains with aggressive assumptions that market share is taken from tech, retail, and other sectors that may suffer from a recession and structural changes which reduce the attractiveness of these sectors.

- Increasing Pay to Recapture Talent: Capitalizing on the recession and closing the pay gap versus other industries to convince those who have left hospitality to return, including those who work in the Gig economy. Challenge: research says people left for culture, flexibility, and inadequate compensation. There is no evidence that changing compensation alone will work. That said, let’s assume hotels increase pay by 20% and owners agree to offer supervisors and above more cash incentives such as profit sharing. Number: 200,000 hiring gains with aggressive assumptions that market share is taken from tech, healthcare, Uber, Airbnb, etc.

- Efficiencies Through Digitalization: Eliminating front-line positions using technology like mobile apps for check in and consolidating departments such as front desk, housekeeping, and restaurants. Challenge: most jobs and pricing power are in full-service, group, and luxury hotels that require service. Number: 100,000 hiring gains.

-

Attracting Talent from Other Industries Hit Hard by the Recession:

An example is retail, which shed 25,000 in August 2022 alone and continues to shed jobs heading into 2023. Challenge: other than the economy sector, hotels have a mixed record of hiring retail, even in functions such as finance. Training costs are higher than anticipated, and turnover risks are extremely high. Furthermore, delivery and logistics businesses, including Uber, are growing with average hourly pay, adjusted for taxes, of 2-3X hourly wages in hotels. Number: 100,000 hiring gains

In conclusion, these optimistic scenarios generate an incremental 500,000 employees. Where does that leave us? Even with the optimistic scenario, the current strategy leaves a gap of 2.4 for the U.S. hotel sector.

Fact Four: The top 16 hotel operators are in a class of their own. Almost half of the top 80 largest hotel operators, representing 70% of branded properties, have abysmal talent and diversity scores.

We analyzed the quality of talent at the top 80 hotel operators, addressing 12,000 hotels and developed an algorithm to rank talent, from the frontline employees to General Managers.

We summarized our findings in the Talent Share Matrix Chart that shows a company’s share of elite talent on the x-axis and the number of properties managed on the y-axis. We classified high-performing hotel operators from a talent perspective, into two buckets: “High Potentials” (talent scores above the median, high growth, and below-average portfolio size and growth) and “Stars” (talent scores above the median, high growth, and above-average portfolio size and growth). A few hotel operators are “Stars” with quality talents that stand above the rest alongside a few notable, small brands and management companies. However, over 50% of the branded hotels are managed by underperforming management companies with below-average talent scores and less than one-star performer per property, whose average tenure is under 24 months.

What about progress in diversity, equity, and inclusion? We also ranked the top 80 hotel management companies for diversity – the proportion of elite talent who are women and minorities in their property level supervisor and above ranks over five years (2017-2022). We then performed regression analysis to ascertain the correlation between the quality of talent and diverse elite talent for the same employers. There is a 92% correlation between a change in the company’s quality of talent score and its diversity talent score. We analyzed these results by brand segment (i.e., economy vs. luxury), product type (i.e., resort vs. airport hotel), and the results were within a 10% confidence interval.

If managerial diversity was a performance KPI with equivalent importance to revenue indexes, many of these operators would be out of business. Furthermore, owner operators – who in theory have the most stakeholder alignment – rank among the worst in DEI. This demonstrates that aside from brands, most of whom are publicly traded or owned by institutional investors, the industry has not made significant strides in diversity at the property management level.

Fact Five: Radical innovations – the broader adoption of the hybrid work model, wholesale changes in job qualifications, and a paradigm shift in hospitality recruiting - could generate an additional 1 million talents, closing the labor shortage to 1.4 million.

- Semi-Qualified “Hidden Workers”: People with service industry experience who are either unemployed, employed part-time or have left the workforce and screened out by legacy HR tech due to the flawed recruiting process and ATS filters that require a college degree. Based on a recent Harvard Business School and Accenture study, we estimate the potential gain to be 500,000 people. The challenges include significantly increased recruiting, training, learning, and development costs of 5-10x per employee to $5,000 per year for the front line.

- Legal Immigration: Qualified hospitality workers such as those trained by hotel chains in countries such as Mexico, the Caribbean, Ukraine, India, and China, where large numbers are seeking to exit. We estimate the potential gain to be 100,000 supervisors and above. The additional costs including visa sponsorship, relocation and housing, and assistance with language barriers, cultural adjustment, and other assistance to be $35,000 per employee.

- Hybrid Work Models: People with service industry experience who need to work from home to take care of family or who had intentionally left the hospitality industry to pursue the hybrid work model that is now the norm in other sectors such as technology and professional services. What if the industry changed its labor model to permit finance, accounting, human resources, revenue management, purchasing, and even General Manager to be hybrid? This would also enable department heads and supervisors on the property to demonstrate their leadership potential. We estimate the potential gain, including attracting new talent into the industry, to be 400,000. Additional costs include accelerated training and development, but there are also potential savings in labor, benefits, and other costs.

While they would be expensive and risky, these radical innovations could generate an additional 1 million talents, closing the gap to 1.4 million. There is only one option to close this gap to 500,000 or less: increasing retention to 75%.

The Solution: Building a Talent Engine of the Future

Clearly, addressing the labor/talent crisis in hospitality requires more than stewardship: significant innovation, including new processes and technologies, is needed to increase retention and attract new talent into the industry in parallel. Hotel operators continue to bet on legacy HR tech, including job sites, ATS platforms, and static internal job boards. These passive platforms filter out 80% of “hidden workers” and use generic AI that delivers inaccurate matches. Research also confirms that across industries, internal job boards have failed to advance meritocracy because they are not widely used by over half of women, minorities, and individuals outside a company’s privileged social networks.

What does the future look like?

On the employer side, imagine a Talent Engine actively pulls in individuals who are hidden workers, legal immigrants, and a hybrid workforce. It uses data and algorithms to help organizations identify stars within their organization who are ready to take on the promotion. For example, it may be the Front Office Manager who is ready to be Director of Rooms or that new Director of Rooms you’ve just hired who outperformed within a brief time and is ready to be a General Manager.

On the talent side, envision employees having fun using the Talent Engine as a portal for learning and development. It becomes their platform for personal branding, accessing career development opportunities, as well as discovering and charting career paths that can be advanced by experiential learning. Talents can showcase their strengths and accomplishments. They can also demonstrate that they are ready for a lateral move or promotion.

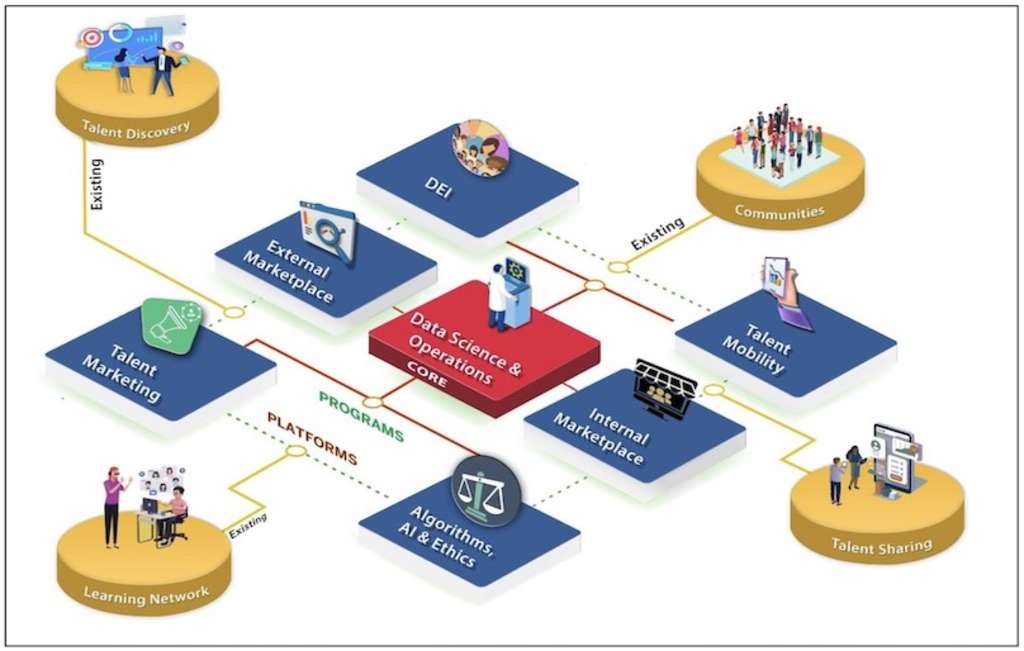

The Talent Engine is powered by AI and data science, and includes the following modular components:

Data Science & Operations – Building scalable solutions to source, rank, and appraise elite talents with leading employers; Writing and testing algorithms that use data science and AI to predict matches between diverse talents and employers in service industries.

External Marketplace – Matching diverse supervisors and above talents from service industries with career opportunities at leading hospitality employers; Includes full-time, contract, part-time, and gig opportunities.

Internal Marketplace – Matching diverse supervisors and above talents from inside multi-unit organizations with career advancement opportunities, including lateral and promotions, across departments, functions, business units, and geographies.

DEI – Closing the diversity gap by sourcing diverse elite and rising talents - 50% women, 33% minorities, and LGBT supervisors - from within and outside hospitality. Providing diverse candidates with career opportunities both internally and externally

Talent Mobility – Providing tools to accelerate career paths, including assessments for elite and rising talents to access both lateral and promotion opportunities inside organizations.

Talent Marketing – Inspirational contents, including GM interviews, talent tier awards, and marketing campaigns that share human stories and promote careers in hospitality. Employers can also create communities based on sponsored content or be organic.

Algorithms, AI, and Ethics – Developing and testing algorithms that generate predictions of talent rankings, tiers, and matches — using data science to generate employer rankings for the overall quality of talents and DEI by company type, region, and brand segments.

Communities/Mentors – Enabling talents to share their stories, chart career paths, form peers and connections, and engage in hospitality-specific communities both internally and externally, including mentorship, references, and reviews.

Talent Discovery – Innovative applications that source hidden workers and talents from outside hospitality, including those outside the traditional workforce, engaging these hidden workers in the external marketplace, learning zone, and communities.

Learning Network/Zone – Providing a hub for experiential learning, including courses and certificates from leading industry providers and employers, and providing an empowering platform for user-generated content from industry professionals sharing best practices and innovations.

Talent Sharing – Brokering talent exchanges between complementary organizations from different geographies or adjacent industries, including both short-term exchanges and long-term talent-sharing deals, enabling fluid movement of people between business partners.

The Path Forward: From Steward to Market Maker

It is widely acknowledged that the hotel industry is not known for R&D or being an early adopter of new technologies. Building a platform where hospitality employees, who represent 300 million worldwide and generate 10% of global GDP, garner recognition and fair compensation for their contribution to the business seems like a daunting task. But the industry is prolific at deal-making and has an impressive track record of integrating new technologies, including reservation systems, channel managers, and loyalty program partners. On the customer side of the service profit chain equation, hoteliers have proven that experimentation is a critical enabler of management processes that build culture. Successful implementation of a Talent Engine similarly requires licensing, integrating, and partnering with many innovative technologies, including start-ups.

The process must be supported by a transformation in the composition and role of the HR function from a “top-down” planner to a facilitator of a “bottoms-up” transparent marketplace that includes internal and external talents. CEOs and Boards should incentivize internal mobility into HR, which must be seen as part of a larger systems approach to executive talent management. Within HR, there should be roles for brand marketers, strategists, deal makers, and technology integrators. It starts with the realization that one of the most effective ways to promote retention, career ambition, and internal mobility is to champion a free market approach by managers, starting at the highest levels of the corporate organization, and incorporate it into the operating units of the organization, regardless of whether they are managed or franchised. But to do this, it is necessary to change the corporate organizational structure and key management processes of the HR function.

The current composition and structure of HR are not set up to innovate. Rather than a tenure-based appointment like academia, HR executives should have “term limits” like those imposed on certain government offices. HR should become a passage rite for every senior executive to be a C-suite leader. Departments such as talent acquisition, training and development, compensation and benefits, and organizational learning should require 2–3-year rotations that include the highest performing directors and VPs from technology, operations, marketing, and other functions, across business units and geographies.

Once corporate HR is reset, the entire corporate office, including strategy, corporate development, finance, and legal, needs to move boldly toward cutting “talent sharing” deals within the industry and with complementary organizations in other service sectors. For example, a hotel brand or operator in part of the industry value chain, such as Extended Stay America (ESA), could develop career paths and exchange talent with a complimentary hotel brand that manages full-service properties, such as Hilton. Talent-sharing exchanges would attract and retain new team members better suited to starting their careers in the budget or limited-service segment and, conversely, those ready to move to full-service or luxury operations. Talent exchanges could also extend into other complementary industries. For example, Hilton could develop a talent exchange platform with Starbucks where its best-in-class regional managers could become food and beverage operators at full-service and luxury hotels. As talent exchanges are implemented in retail, education, and healthcare industries, they could help manage labor supply and demand changes by developing a multi-disciplinary workforce.

By partnering with software companies to build a Talent Engine, hospitality leaders can create a virtuous talent cycle: an employer brand that attracts people and strengthens the industry by providing career opportunities, both inside organization and externally. By adopting this new perspective, the industry can begin to attract people who are looking for growth and value culture as much, if not more, than compensation. Continuously linking culture, leadership, and mobility can increase the talent pool and retention. The result of these efforts can be an organization that can confidently invest in its people who reach their human potential and become industry leaders themselves.