Coping with Crisis: Tackling Hospitality Labor Shortages Amid Pandemic and Tech Advances

Why High-Tech and High-Touch is the Only Way Forward in Hospitality?

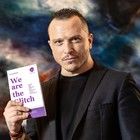

Information Technology — Viewpoint by Max Starkov

According to a Perkbox survey, Hospitality is the fifth most stressful industry to work in, with 64% of employees suffering from workplace anxiety. Therefore, it is not surprising that a significant number of hospitality workers are reconsidering their employment situation and evaluating different career options. And, if possible, the COVID pandemic made things even worse: the 2022 US Job Market Report demonstrated that not only 45% of hospitality workers who have remained in the industry report lower job satisfaction now than before the pandemic,

but also that around 25% of the ones who quit the industry are not willing to work in it again.

Reasons are numerous: from low pay to lack of benefits, from schedule inflexibility and unpredictability of working hours to the pressure of dealing with demanding guests. We have to come to terms with it: the grass is, indeed, not as green on the hospitality side as we think it was. A recent study by DW highlighted how a good portion of workers from hotels and restaurants moved to the retail sector post-COVID and that such workers are difficult or impossible to win back because they have become accustomed to regular working hours and weekends off.

All the above-mentioned reasons contributed to one of the major (if not the major) problems in our industry today, one which cannot be easily solved, at least not with conventional measures: labor shortage. And if some studies suggest that Hospitality has been understaffed at least since the mid-2000s, the situation has never been more critical. It seems the only way out of this situation can be found in one of the following measures:

1. Create workers.

In order to "create" new workers, the industry should focus on training them first. However, at least from a purely academic perspective, the situation is, at best, alarming. The majority of papers published on the subject point to the identical, dire conclusion: 1/3 of hotel management and food and beverage services students decide not to pursue a career in the industry.

2. Import workers.

Currently, immigrants make up 22% of the hospitality workforce, so "importing" workers can be a viable solution, yet not a definitive one, especially in countries with strict immigration policies. Think of the UK, for example: due to Brexit's new visa income requirements, many EU workers have either chosen (or been forced) to leave the country. To put things into perspective, it's worth quoting a report published by The Independent, which found out that "up to 75% of London's hospitality workers (pre-Brexit) were from the EU.

3. Replace workers.

In 2020, the number of births in Japan fell to 840,832, the lowest since 1899. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe called it a "national crisis," because, if the trend does not revert, by 2050, the country will have double the number of people over 70 compared with those aged 15-30. Apart from the social and ethical implications, the shrinking working-age population also creates a highly problematic scenario in terms of labor shortage. Japan, however, is still the second-largest developed economy in the world and, interestingly, also the second most robot-intensive economy (and the first in industrial robot manufacturing). After WWII, automation played an essential role in Japan's economic rise, and proved to be a valuable ally in dealing with the country's demographic decline. In 2015, the Japanese government approved a document called the "New Robot Strategy" to encourage the research and development of robots in pretty much any field.

If the idea of "replacing" biological workers with artificial ones is not (yet) entirely accepted, it is also true that we tend to have a cognitive bias towards robotics. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines the term "robot" as "a device that automatically performs complicated, often repetitive tasks." However, when we think about robots, we tend to rely more on pop culture. In Hospitality, however, the use of humanoid robots is sporadic and not (yet) particularly effective. The story of the Hen-na Hotel in Nagasaki is a fitting example, as the world's first robot-staffed hotel had to "fire" half of its robot workforce due to malfunction. It's easier now,

a (human) staff member stated, that we're not being frequently called by guests to help with problems with the robots.

The use of AI or RPA is way more functional in Hospitality: software (and not hardware) robots or models that can perform repetitive tasks otherwise done by humans.

According to McKinsey, "about 60% of all occupations have at least 30% of constituent activities that could be automated." Hi-tech, therefore, should not be seen with techno-skepticism but with straightforward, pragmatic, entrepreneurial realism.

During his 2020 presidential campaign, Democratic candidate Andrew Yang predicted that technological advancements (especially in the field of AI) could result in one in three American workers losing their jobs by 2032. Yang's solution to this (presumed) work crisis was what he referred to as the Freedom Dividend, which is widely known as the universal basic income. Advocates of UBI's list is ever-growing, with influential names such as Tim Berners-Lee, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, Bill Gates, Larry Page, Ray Kurzweil, and Elon Musk. However, data seem to suggest that companies investing in new technologies tend to hire more people than their peers who do not, so the problem of robot-induced unemployment, at this stage, is purely speculative and not backed up by any substantial evidence. Right now, the application of tech in Hospitality (and any other industry, for that matter) has been proven to be highly effective in managing repetitive, routine, and tedious tasks, increasing the cost-efficiency and value of hotels.

At a closer look, automation allows human staff to concentrate on what's really important: managing unusual situations, offering assurance, and adding compassion to the interactions with guests.

by

by